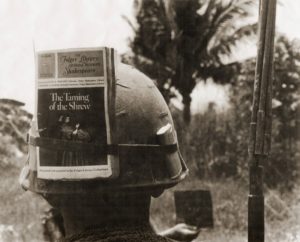

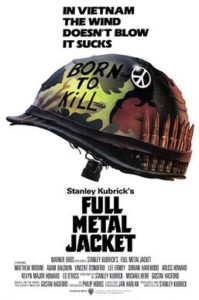

You can find this treasure in the Folger archives – a photograph of a soldier marching through Vietnam, a copy of Taming of the Shrew stuck in his helmet (Fig. 1). The photo might recall the poster for Kubrick’s 1987 war film Full Metal Jacket, featuring a helmet emblazoned with both the peace symbol and the slogan “Born to Kill” (Fig. 2). So what is this young Shakespearean in Vietnam trying to do with such a conspicuous display? Is he bringing Renaissance art to a war zone that desperately needs it? Is he smirking at the associations of “grunt” by reading Shakespeare in his spare time? Or perhaps he’s considering the specific play – something about the mistreatment of Kate in the middle of the war? Just what does he think of the torture that brings Petruchio’s wife to “proper” behaviour?

Shakespeare had been to war before, most famously in Laurence Olivier’s Henry V. The film, released in 1944, begins with a dedication to the troops, and according to legends, Winston Churchill implored Olivier to make the film specifically to inspire a war-weary nation. The film does its part by glorying in martial heroism. But following the observance of Armistice Day on November 11 – a centennial anniversary – we suggest a different approach to Shakespeare, not as a warrior but as a pacifist. The image of a young man carrying Taming of the Shrew during the Vietnam War may not be the most iconic protest image of the 1960s and 70s, yet it strikes a compelling contrast. Amid the violence and gunfire of modern warfare, one might find time to read a few lines of Shakespearean comedy. And that might just be pacifism above all else.

One attitude in Shakespeare’s day toward peace treats the absence of war as dangerously lethargic. In The Prince, Machiavelli argues, “A prince […] should have no other object, no other thought, no other subject of study, than war.”1 Any other concern makes the ruler weak and vulnerable. He continues, “It is clear that when princes have thought more about the refinements of life than about war, they have lost their positions. The quickest way to lose a state is to neglect this art.”2 Francis Bacon expands that reasoning beyond the single ruler, to an entire people, when he writes, “a just and honorable war is the true exercise [because] war is like the heat of exercise and serves to keep the body in health. For in a slothful peace, both courage will effeminate and manners corrupt.”3 For these Renaissance thinkers, peace is nothing but an idleness degrading its participants. Against peace, then, is the argument that war is “doing something” and, even more simply, war is the engine that drives the world forward. The study of war, consequently, goes without saying; Machiavelli calls it the only subject worth studying.

The field of Peace Studies begs to differ. Johan Galtung in his first editorial for the Journal of Peace Research in 1964 advocated re-thinking the relationship between peace and war. Negative peace, he said, implies “the absence of violence, the absence of war” – that is, it looks at the conclusions of conflict.4 As such, it leaves researchers without much to do. Positive peace looks for something else: “the integration of human society,” meaning the advocacy of diplomacy, equality, or non-violent solution. “Positive peace,” at its most fundamental, suggests that peace is complicated and worthy of study. Far from “slothful,” this peace becomes active, exciting, and even the stuff of drama.

So could Shakespeare – a dramatist seeking out interesting plots 400 years before Galtung’s editorial – be considered an advocate for positive peace?

In the earliest history plays, it seems unlikely as characters valorize the war hero. Even before Shakespeare has written Henry V, that warrior king looms over all activity. Henry VI Part I opens with his memory: “His sparkling eyes, replete with wrathful fire, / More dazzled and drove back his enemies / Than midday sun” (1.1.12-14). This is the hero who “ne’er lift up his hand but conquered” (1.1.16). Like Olivier or Churchill, the wartime leader does well to stir the imagination with this image. Bemoaning lost territory and the decline of England’s military might, the Duke of Bedford puts a fine point on it: “Henry the Fifth, thy ghost I invocate” (1.1.52). The historical king’s prowess in battle becomes the subject of nostalgia and a talisman to protect the English.

The Henry VI plays chart the descent into civil war, a historical course that undermines the victories of Henry V. And the characters express keen awareness at their failure to live up to the ghost invoked in the first passages. The hero Talbot dies alongside his son, but not before the father issues a dire warning: “In thee thy mother dies, our household’s name, / My death’s revenge, thy youth, and England’s fame” (4.6.38-39). The future is over, but the ghost of Henry V still lingers in the shared memory of the English populace. Sir William Lucy, watching the outbreak of civil war, laments “the vulture of sedition” that undoes the conquests of “That ever-living man of memory / Henry the Fifth” (4.3.51-52). The death of father and son is moving and dramatic, a failure to live up to the model of the war king. The memory, however, remains. And with it, the image of bloody conquest.

By the time of Shakespeare’s late career, alternative models of thought were emerging. The ghost of Henry V no longer serves as the only ideal; indeed, we see plays celebrate pacifists in a new mold. Take Cymbeline. That late romance finishes with a battle and the heroic military action of male characters. Yet the king’s daughter, Innogen, serves as the reconciliation. Her cross-dressing – and service as a page – introduces the effeminacy that Bacon warned about as a negative aspect of peacetime. In this, though, it undermines the value of the final battle between Rome and England in order to enable powerful political alliance. In front of her long lost brothers and Posthumus, her betrothed, the king Cymbeline remarks on her appearance:

Posthumus anchors upon Innogen,

And she, like harmless lightning, throws her eye

On him, her brothers, me, her master, hitting

Each object with a joy. (5.6.393-97)

He renders lightning, a potentially violent image, a source of reunion and forgiveness. Whatever is hit makes not further bloodshed but joy, so much so that the play concludes with Cymbeline’s vow of peace. He invites his Roman foes to ratify a treaty, exiting the stage while looking ahead to pacifist futures. “Never was a war did cease,” he says, “Ere bloody hands were washed, with such a peace” (5.6.484-85). Male heroes may thrive in the war, but in Cymbeline, this moment appears to have passed. Their ghosts will not be invoked to lead to new conquests; instead, Shakespeare allows his audience to re-imagine British history, maybe without the need for Henry V at all. And, today, we are left with the echo of Shakespeare: the last word of one of his last plays was “peace.”

As Shakespeare finished Cymbeline, he also would have understood that his new monarch, James I, was particularly invested in British pacifism, even being deemed the Rex Pacificus (King of Peace). In a book titled The Wonderfull Yeare (1603), the author Thomas Dekker wrote of the new king,

The Cedar of [Elizabeth’s] government which stood alone and bare no fruit, is changed now to an Olive, upon whose spreading branches grow both Kings and Queenes. Oh it were able to fill a hundred pair of writing tables with notes, but to see the parts plaid in the compass of one hour on the stage of this newfound world!5

James I has heirs, unlike Elizabeth, but his branches are notably olive branches. Peace is growing, fostering a “newfound world.”

Shakespeare surely knew this reputation as he set down – in collaboration with John Fletcher – the conclusion of Henry VIII. Like Cymbeline, the play deals with anachronism as the characters are treated to a prophecy of Elizabeth, the queen already gone by the time of the play’s performance. During her reign, we learn “every man … shall sign / The merry songs of peace to all his neighbours” (5.4.34-35). And when she passes, James I will emerge like a phoenix:

Peace, plenty, love, truth, terror,

That were the servants to this chosen infant,

Shall then be his, and, like a vine, grow to him. (5.4.47-49)

The histories invoked here celebrate peace, not as a slothful corruption but as a period of plenty and an ideal past. Shakespeare imagines a golden age, couching it as a prophecy for characters who can learn to see peace as worthwhile, as a re-appropriation of the devastating action in the early history plays.

Commemorations of peace have dominated headlines in Europe and the United States. Macron and Trump have exchanged barbs on the value of nationalism, but it’s also worth noting that Macron invoked ghosts of his own in his Armistice Day speech. Speaking of all who perished at war, he says, “Each of them is the face of that hope for which a whole young generation agreed to die: that of a world finally peaceful again.”6 Macron speaks to a history bending toward peacefulness. Despite the failure of the League of Nations, he knows the effort continues in the United Nations. He finishes by saying, “This fraternity, my friends, actually calls on us to wage the only battle worth waging: the battle for peace, the battle for a better world.” Like Innogen, he inverts the language of the military and makes pacifism the furthest thing from sloth or weakness. As in Shakespeare’s late histories, peace reigns, and it is action that creates a new world.

Perhaps the soldier in Vietnam would have liked that possible future.

John S. Garrison and Kyle Pivetti are authors, most recently, of Shakespeare at Peace.

1 Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince, Second Edition, trans. Robert M. Adams (New York: Norton, 1992), 40.

2 Ibid., 40.

3 Francis Bacon, Francis Bacon: The Major Works, ed. Brian Vickers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 402.

4 Johan Galtung, “An editorial,” Journal of Peace Research 1.1 (1964): 2.

5 Quoted in James Doelman, King James I and the Religious Culture of England (Woodbridge: D.S. Brewer, 2000), 87.

6 M. Emmanuel Macron, “Emmanuel Macron’s Speech at Commemoration of the centenary of the Armistice,” Permanent Mission of France to the United Nations, onu.delegfrance.org, accessed 19 November 2018.